Claire Marshall, Founder of If Labs, set the stage for the future at the imagined ON CORE 2035, delivering a powerful message from 10 years ahead. She worked with our ON ecosystem ahead of the event to explore the future of research and its profound impact on Australia, inspiring us all to think beyond the present and embrace the possibilities – and responsibilities – that lie ahead.

Claire Marshall’s story from ON Core 2035:

For the next 12 minutes, I am going to take you on a journey to 2035. Take a deep breath and let’s jump into the future.

————————————————————————-

Welcome to the 2035 ONCore conference. Today I’ve been given the opportunity to speak about the last ten years of the program, however, I promise it won’t be a history lesson but rather a lesson in evolution. How one powerful story can evolve a whole ecosystem.

10 years ago on this very stage, a founder was pitching a start up, called Symbiosia, but in a funny way it wasn’t the technology that captured everyone’s attention, it was something that she said.

She said, science has always had a relationship with stories. As Thomas Kuhn explored in his book the Structure of the scientific revolution, the paradigms we think through impact the science that gets done. Of course the science that gets done then impacts the paradigms we think through. An example of this is in the year 2000 when scientist and atmospheric researcher Paul Crutzen stood in front of a conference of his peers in Mexico and declared that the climate data he was seeing showed that we had moved out of the safe holocene period. We had irreparably changed the climate with our actions. He proposed that our epoch receives a new name – the anthropocene – the age of man. This was a pretty big paradigm shift.

For the next 25 years this is the paradigm that a lot of us looked through when conducting research. But the founder on stage wondered if this was the story we should focus on. She said her children responded better to being told what to do, not what not to do. She asked – what if we told a story about a future epoch – the one we were trying to aim for? The symbiocene (a term coined by Glenn Albrecht) – a time where we lived, created and worked in symbiosis with the natural world.

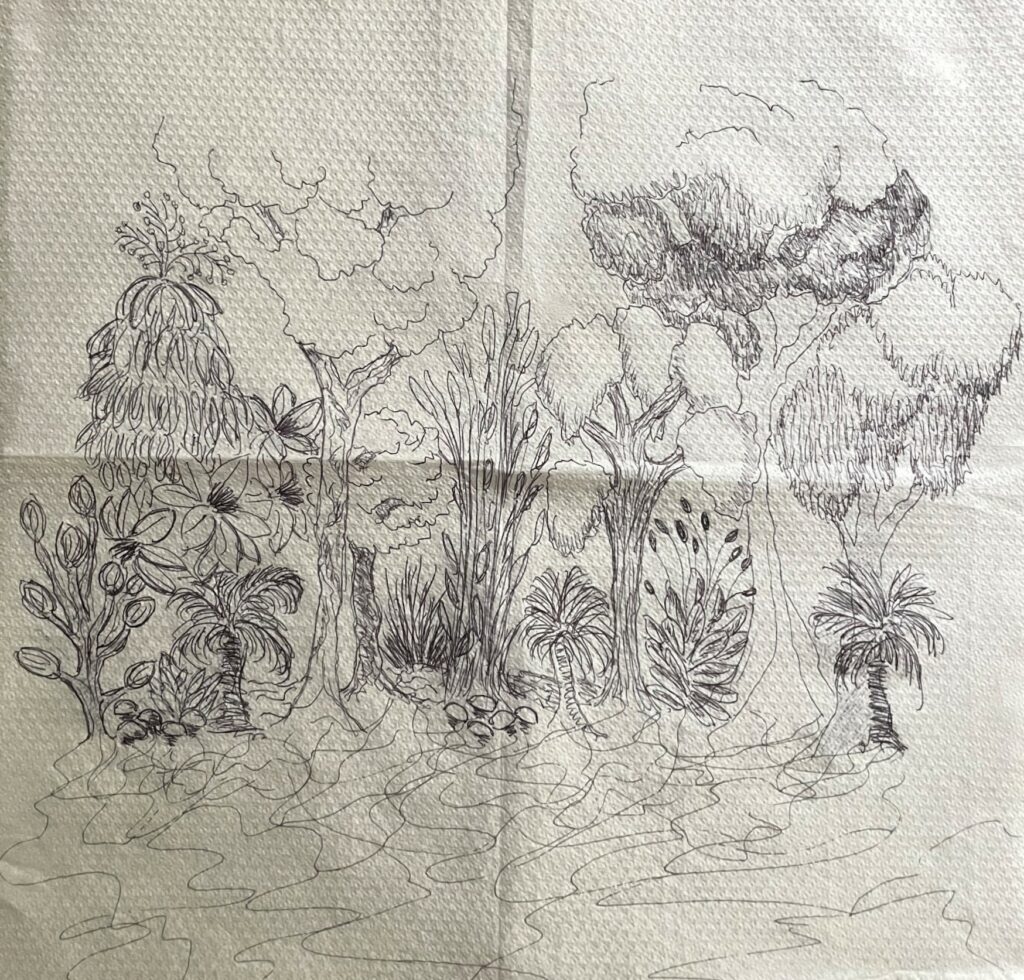

It was a powerful idea, and she got a pretty big round of applause. But she also planted seeds in people’s minds (including mine). By the end of that day there was a group of people buzzing off the idea. They went out for dinner afterwards eager to talk about what this could mean. They talked about seeing themselves as a forest eco-system, where diversity is a sign of health. Researchers, founders, investors, TTO’s, policymakers, media – all playing different and complementary roles in the forest family. The tallest trees – in the eco-system – the mother trees whose crowns reach the sun – sharing their sugars with the ones that were growing in their shadows – all facilitated by the mycorrhizal networks.

In fact I have the napkin on which they drew this here.

That late night brought with it big ideas. They talked about revolutionising how deep tech gets funded with loans that were as patient as the mother trees, funding with no return until the company was tall enough to reach the sun on its own. They talked about governments creating regulatory sandboxes, sections of the forest where new incentive systems could be tested, and old regulations evaluated. A place for creativity and intuition, a place that was safe enough for big ideas to be born. They talked about old wisdom. Indigenous knowledges and the voices that held them being seriously listened to and acted on.

They talked about stronger, more collaborative mycorrhizal networks that connected the trees to each other, across species, across countries – so that no one needed to ‘change the world’ on their own, but just join their piece of the puzzle to those around them.

They were excited. The seeds planted in their mind had blossomed into a vision of the symbiocene. But as excited they were, they knew the political wind wasn’t blowing their way. These new ideas if launched now would simply fall on dry earth.

But the group did not get discouraged. They decided to think strategically. How could they create this epoch in the current one, one seed at a time?

They started by reaching out to the successful ASX-listed companies now commanding their industry. These tall mother trees were spending on R&D, but not in Australia. The group asked – could you not support the forest at home?

One ON program alumni Rainstick jumped at the chance. Country was their teacher, and had taught them how to mimic the electric effects of lightning to stimulate plant growth without fertilisers. The symbiocene was part of their vision too. Next came Dragonfly Thinking – another ON program alumni. Their focus had been on using AI to help people understand complex problems in more holistic ways, but they saw that there was another opportunity. What if their AI technology was able to help people listen to living systems so that they could understand complex problems through the eyes of the human and non-human alike?

At the same time this was happening, a new story was developing in higher education institutions.

A few universities started talking about themselves not as places that made job-ready graduates but as places where the world’s biggest problems get tackled. Trans-disciplinarity was the focus, with students from across disciplines working together on complex problems. They introduced mandatory impact training modelled on the ON program for all students. They introduced new PhDs of impact and sabbatical-like funding for researchers who wanted to take their research into the market.

And in one of my favourite initiatives, not only did they hire more tech transfer officers, but they also part-funded a series that brought their work to our screens. I loved seeing the teams develop in different ways, some passing on their research to entrepreneurial teams, some choosing to go on that journey themselves. All the time the TTO’s carefully orchestrating things. This show actually became quite a big thing but its main impact was that it made the tech within universities visible. It showed university and industry working together, with reciprocity built into R&D contracts. It also highlighted the difficult political climate and the big risks investors had to take to fund much-needed deep tech.

Luckily investors seemed to show up. It seemed there was a new story spreading in the investment world as well.

Many prominent companies started to give a seat on the board to “Mother Nature” usually an ecologist or biologist. This meant that company decisions were evaluated based on their impact on living systems, not just shareholders. Some companies went further and declared that the Earth was their only shareholder. Of course, this wasn’t a new thing, Patagonia did it in 2022, but by 2030 it was starting to be the norm. More and more the conversation became not about personal legacy, leaving your children a huge inheritance or putting your name on a building, it became about collective legacy fuelled by cathedral thinking. The question became what seeds can we nurture and care for even if we don’t live to see them bloom?

Meanwhile, the general population started to experience a shift too. Sick of polarising politics people started to demand more transparency. More Climate Strikes initiated by students started to raise the question of who has a duty of care for their future?

When the next election rolled around, the political winds had changed. It was 2030 and a scientist who had worked at CSIRO and co-authored many climate reports, ran for the highest office on a platform of care for Country and for each other. She spoke passionately about the benefits of good research, of clear and honest conversations that were based on facts not self-serving narratives.

When she was elected Prime-Miniser in 2032 a lot of things happened quickly. The ideas that had been growing in the forest – their time had come.

The first move was tax reform, and a tightening up of the loopholes that let Australia’s largest companies get away with taking from the country but never giving back. This fuelled massive spending on R&D with a focus on uplifting Indigenous founders who used traditional knowledge to care for Country. Fossil fuel subsidies were abolished and the money was spent resourcing deep tech that would help Australia adapt to the changing climate. A raft of new legislation provided incentives in almost every industry to work towards not just sustainability but regeneration. Many innovative Australian companies and entrepreneurs who had been forced to relocate overseas, started to return home.

Then in a huge move, the new Prime Minister declared that Australia needed a new story that included the hopes and dreams of all its people. Researchers across Australia were tasked with conducting a nationwide conversation with just one question: what kind of Australia do we want to gift future generations? The answers were not surprising. No flying cars or floating cities, but a lot of clean air and clean water.

Our dreams were put into legislation and an independent Future Generations Commissioner was appointed to make them a reality. Sitting outside of government, the commissioner weighed in on every piece of legislation. They sought bipartisan support for legislation that would run over more than one political term. This security and focus led to global alliances where Australia partnered with other countries to become the global leaders in specific parts of the climate solution. Our puzzle piece fitting into theirs.

Our Australia of 2035 looks different than it did 10 years ago. Maybe it’s because of some of you in the room, but we can never be sure, as we have learnt to see the forest and not just the trees. While Australia looks different, so do we. We have given up ‘personal branding’ and ‘personal achievements’ they now just feel very anthropocentric. The symbiocene has required us to de-centre ourselves. To understand that we need to speak for the trees, and the bees, and the seas.

While today in 2035 we might not yet be able to claim we have entered the symbiocene, its paradigm has changed not just what we do, it has changed us.

————————————————————————-

From back in 2025, I want to acknowledge that this story today has been written with the help of a lot of people. I want to leave you with a Barbara Kingsolver quote ‘We have done hard things before. And every time it took a fight between people who could not imagine changing the rules, and those who said, “We already did. We have made the world new.”

In 10 years, someone will be standing on this stage telling the story of the ON program – let us make it the story of a forest ecosystem evolving, growing and creating impact together.

Read ON Core 2025’s letter to the future, developed by Claire Marshall and ON Core participants.